Fiesch is – in theory – vulnerable to föhn from the north as well as the south, but this word is generally used in German-speaking Switzerland to refer to conditions with a southerly origin. Also, some pilots here apply the term somewhat loosely to any adverse winds on the lee side of a mountain range (which are, after all, what we need to be concerned about) so for the purposes of explanation, I have adopted those two conventions here.

Although getting caught in full-on föhn in these big mountains would be unpleasant and dangerous, a forecast of “mild föhn tendency” is often associated with excellent flying conditions here, particularly for long one-way XCs to the east, so you may find that you are having to balance this risk against the potential for a good flight. Also, föhn may develop gradually during the day, requiring a decision as to whether to continue or abandon flying, so it’s important to be able not only to predict it, but also to recognise its early manifestations.

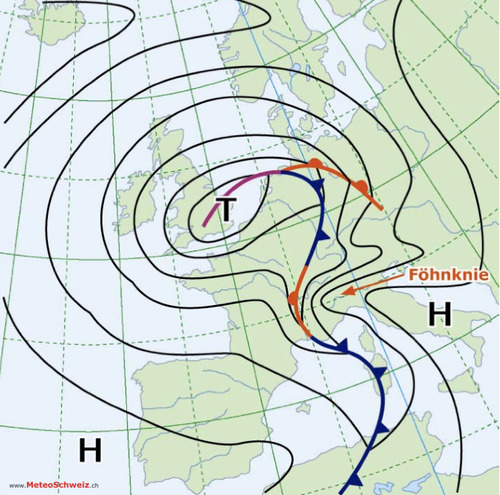

When assessing the risk of föhn, I start off by taking a glance at the synoptic chart to get an idea of the general weather situation and to put other information in context. An approaching Atlantic depression and cold front usually guarantees its development, which can often start even when the front is still located in the western half of France. This chart shows the typical pattern, with the classic “föhn knee” feature in somewhat exaggerated form:

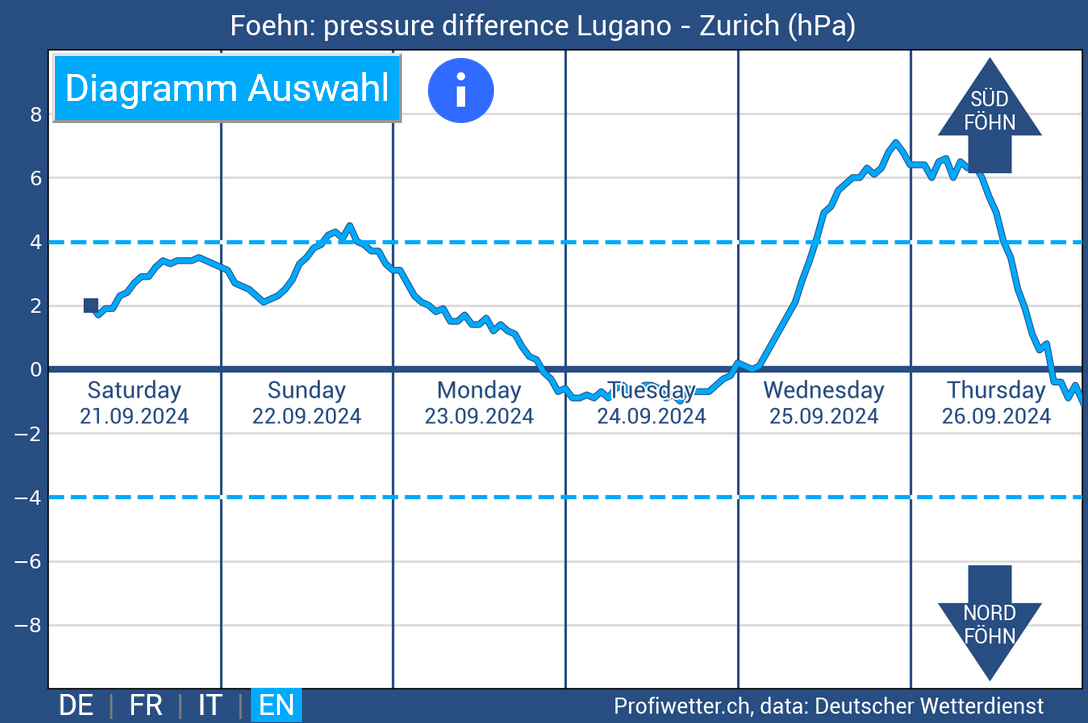

I then look at a prediction of ground level north-south “overpressure” (explained on a separate page) – the difference in atmospheric pressure between Lugano (to the south) and Zürich (to the north), which is available at Profiwetter:

It’s said that the risk of föhn becomes significant if the value exceeds 4 hPa. However, it really isn’t as simple as that; on that basis 21.09.24 should have been ok, but as the two charts below (from that date) show, it wasn’t. In the spring, 2 hPa can be enough, and higher humidity (or precipitation) on the side of the Alps from which the airflow originates can also increase its likelihood. Another issue is that the pressure difference at altitude may be completely different from the value at ground level (but impossible to determine). In August 2024 there was even one day when this chart showed 5 hPa of north overpressure, but south föhn arose around Fiesch because of a significant gradient in the opposite direction higher up. I have also often noticed that a rapid change of pressure in either direction is associated with unexpected winds, not always because that indicates some general weather disturbance around.

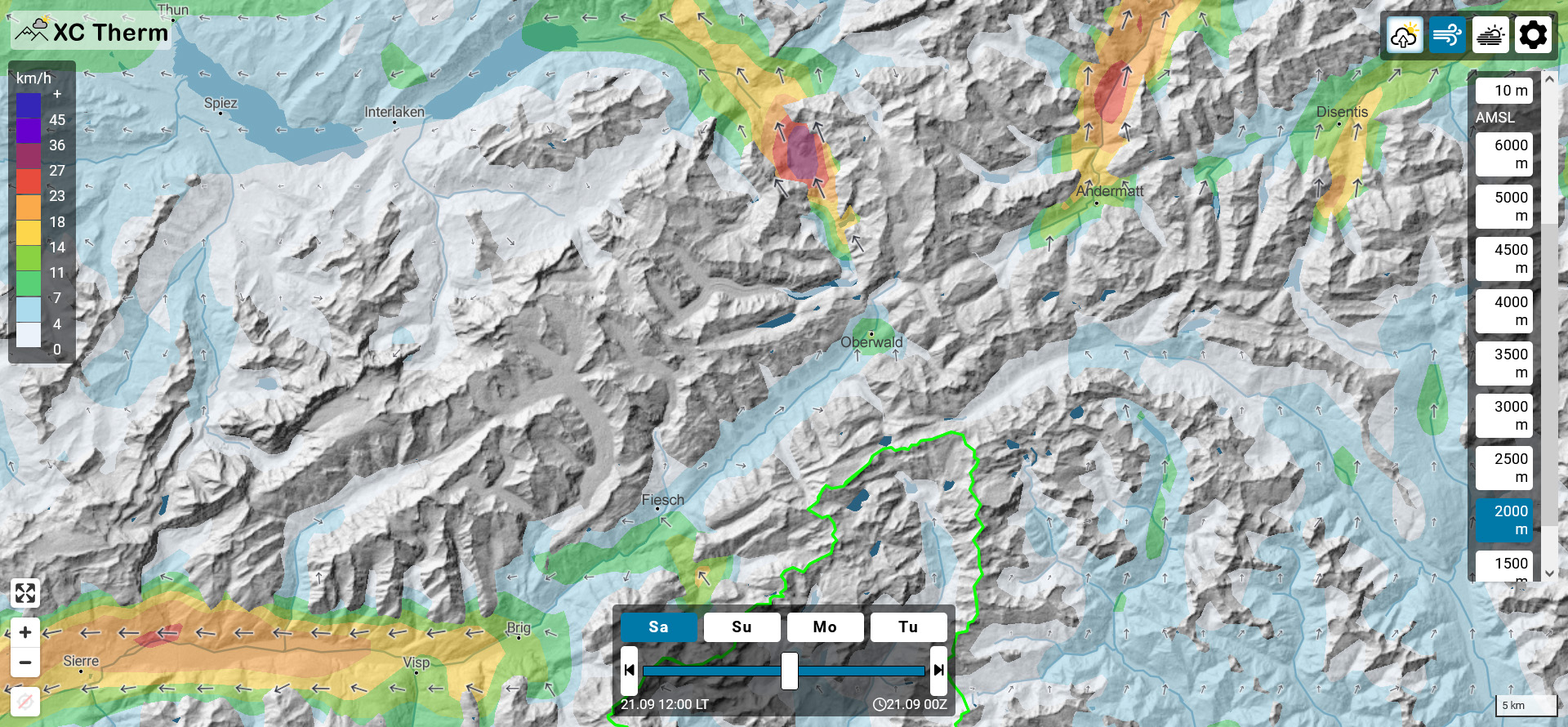

Next, I check out the wind forecasts at XCTherm, in particular the charts showing the flows at 2,000m. This example shows unmistakeable signs of föhn, with an easterly breeze at Visp (when the normal direction would be from the west), a southerly flow in the Haslital to the north of Oberwald (where the Grimseler would usually be blowing from the north), a southerly breeze to the north of Andermatt (when a vigorous northerly is almost always present on a thermic day) and a southerly wind blowing into Disentis (instead of the usual easterly):

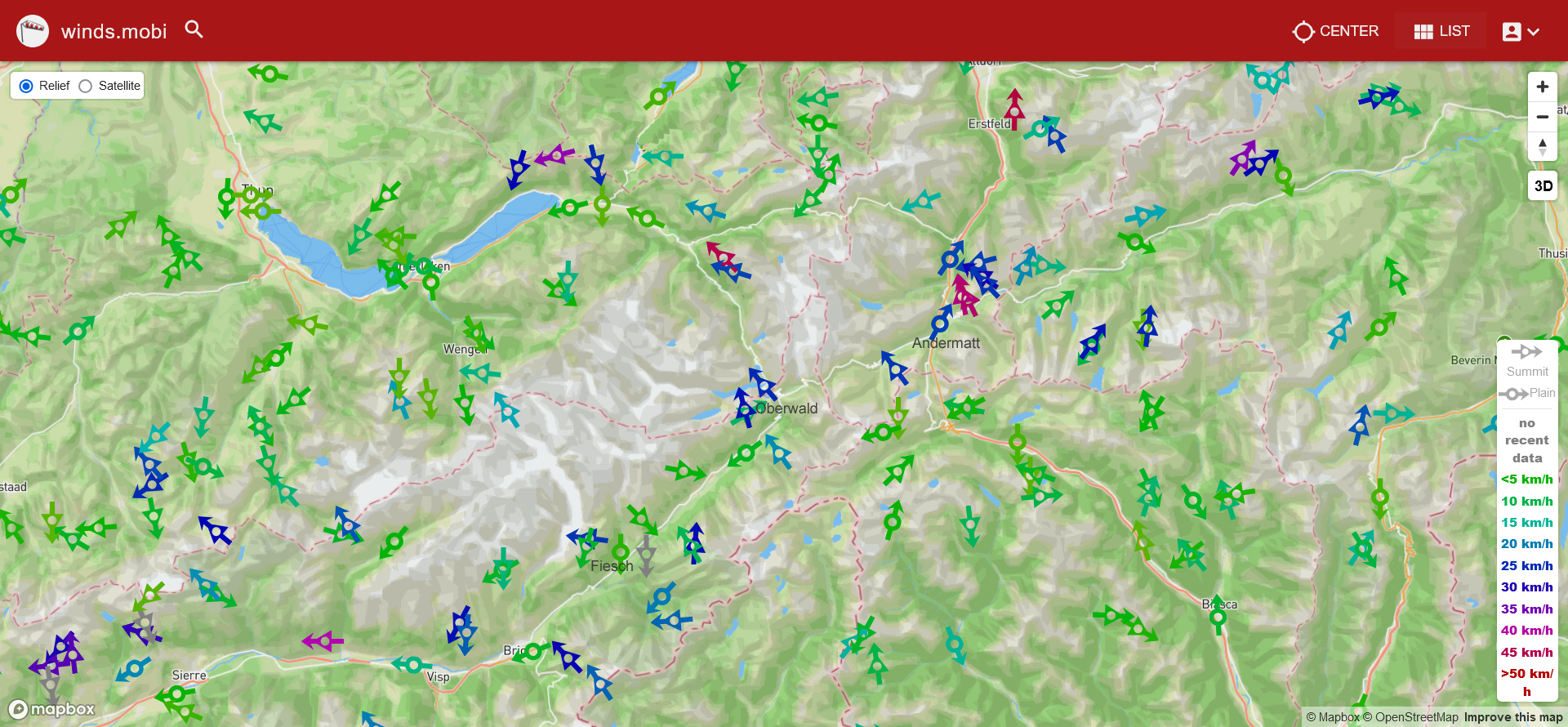

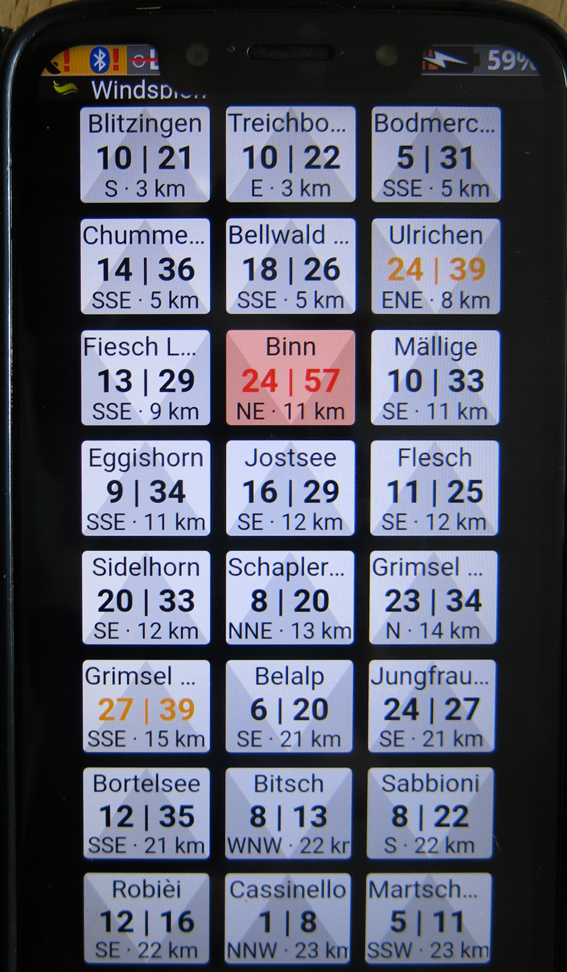

In the morning, an overall review of the weather stations may also reveal föhn, as shown here:

The important features to note on this chart are the same as those in the XCTherm prediction, and also in particular how the winds at lower altitudes in the valley are stronger than those at the peaks, and blowing downwards, not upwards as one would expect in thermic conditions.

Once you are at any of the Fiescheralp takeoffs, you have a good view of the mountains which form the border between Switzerland and Italy, around 13km to the south-east. It’s quite common to see “föhnmauer” there – a wall of cloud on the ridge – even on days when föhn doesn’t materialise. Take some time to watch this closely; when the cloud appears stationary, the day may well be spared, but if you can see it pouring down the slope towards you like a waterfall, then it’s likely that the flying conditions will be significantly affected (and I would be wondering whether I should be flying at all).

Typical appearance from Heimat takeoff of “föhnmauer” – a wall of cloud on the ridge across the valley to the south-east of takeoff

Live readings from weather stations enable you to see if föhn is developing. Local tandem pilots often use their smartphones on the way to takeoff to check out values at Binn, Ulrichen, Visp and Rosswald; winds of more than gentle strength with a significant easterly component ring alarm bells. The wind speed at Binn is the most relevant to Fiesch itself, with 30km/hr considered by the Flying Center Oberwallis as the upper limit of safety (but note that the downslope direction here, indicating south föhn, is from the north-east). When you are flying along the Urserntal, it’s relevant to monitor the readings at Andermatt, Gütsch and Bälmeten.

If you are airborne around Fiesch and hazy conditions suddenly clear when the possibility of föhn has been predicted for later, this is a sign that it may already have broken through down in the valley and suggests that you have outstayed your welcome. The safest option in this situation may be to land at takeoff level. A more typical scenario is that increasing wind readings or turbulence are approaching your “time to call it a day” threshold, so you decide it’s best to land. In this situation, you should try to avoid locations exposed to wind from the side valleys mentioned above. The Fiesch landing field is not exposed to the wind from the Binntal, but Lax (safer if Bise has broken through) can be horrendous in that situation. It’s best to avoid landing near Ulrichen (or further east) but sufficient wind blowing out of the Agenetal there to cause concern will often be associated with thermodynamic lift on the slope directly opposite this outflow enabling you to gain sufficient height to reach Ritzingen, which is likely to be your safest option. You should not overfly the Münster sailplane runway low (in June, July and August) but if it appears deserted, prioritising your safety may appeal. Near Brig, Bitsch is less exposed to the wind blowing down from the Simplon pass than options further west. In the Urserntal, Zumdorf (half way between Realp and Hospental, identifiable from the air from the gravel works) is probably your best bet, and near Disentis, a downwind dash to Trun is likely to be safer than landing there in föhn.

An anomaly to bear in mind is that föhn is often associated with a breeze from the north-east in the Fiesch landing field, for which there seems no obvious explanation.

A case study, including various charts, illustrates some of these points.

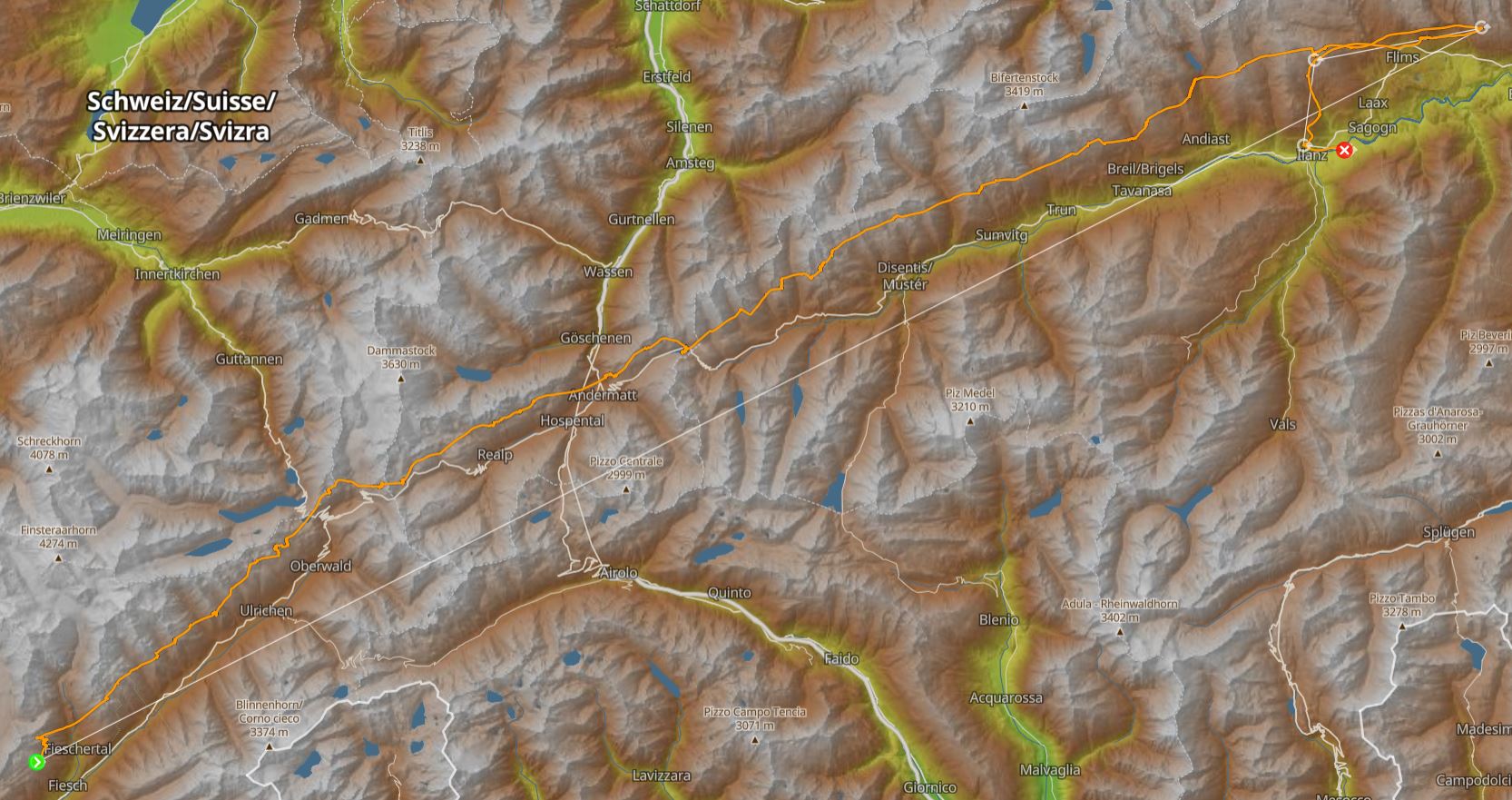

I hesitate to include an example flight here, as flying with föhn around is not to be recommended. This one took place in borderline Lugano/Zürich south overpressure of 4 hPa, which certainly resulted in föhn at valley level in Andermatt at the time I overflew the village, and made me somewhat apprehensive about my landing options, but led to no problems higher up or when I landed near Ilanz:

Flight in borderline föhnish conditions (click here for 3D visualisation, here for XContest details)

The header image (showing föhnmauer in the Gotthard pass) was taken on another day with excellent conditions for flying from Fiesch over the passes, to Flims.